Flowable composite resins made their debut in the dental world in 1996, but they didn’t make a very big splash. Originally developed to simplify the placement technique and expand the range of clinical applications for resin composites, these first-generation flowables failed to impress as clinicians quickly found that they demonstrated poor clinical performance and did not achieve predictable, long-term results because of inferior flexural strength and wear resistance compared with conventional hybrid composites. However, over the past 20 years flowable composite resins have been re-evaluated and redesigned with extensive improvements to their chemistry in order to increase their usability in dentistry.

Preoperative facial view demonstrating existing defective and unesthetic resin composite restorations.

Postoperative facial view of the central incisors after restoration using hybrid composites.

The most dramatic and clinically effective improvement between the first- and next-generation flowable composite resins is the filler component. Next-generation flowables make use of filler components with finer particle size, shape, orientation, and concentration. The result is a resin composite with dramatically improved mechanical properties, making the materials comparable to conventional hybrid composites. The improved filler component also improves the esthetic and optical qualities of the flowable by using a polychromatic double-layer effect similar to the color relationship between natural enamel and the underlying dentin. These flowable resins can be layered over each other for subtle color combinations that give esthetic dentists unparalleled freedom in developing natural-looking, esthetic restorations.

A 12-year postoperative view of the previous case.

View at the 17-year follow-up.

But next-generation flowables didn’t just improve upon their own recipe; according to recent studies, certain flowable composites (G-aenial Universal Flo, G-aenial Flo, and Clearfil Majesty Flow) have shown significantly greater flexural strength and a higher elastic modulus than the manufacturers’ corresponding conventional composite materials. Combine these benefits with the easier and more convenient application technique—flowable composite resins were always intended to improve upon the scoop-and-pack technique of conventional hybrid composites—and you have a composite material that can create predictable, customizable, durable restorations chairside.

Understandably, some clinicians who gave the first-generation flowables a chance may be reluctant to offer the benefit of the doubt to this new generation. However, current research and the clinical experience of those who have tried the next-generation materials proves that the technology today is not the technology of 20 years ago. As Dr John M. Powers has stated, the flowable today is not really a flowable—it’s an injectable composite. The next-generation flowables are proving themselves to be viable fulfillments to those promises manufacturers made in the past. They can be used for anterior and posterior composite restorations; sealants and preventive resin restorations; fabrication, modification, and repair of composite prototypes and provisional restorations; intraoral repair of fractured ceramic and composite restorations; elimination of cervical sensitivity; resurfacing of occlusal wear on posterior composite restorations; development of composite prototypes for copy milling; and the placement of pediatric composite crowns. There is seemingly no end to the ways a creative dentist can use these new flowables.

Preoperative facial views of the maxillary anterior segment. The 26-year-old patient presented with multiple Class IV fractures on the maxillary anterior teeth following a skateboarding accident.

A diagnostic wax-up was created to restore the original form and contours of the incisors.

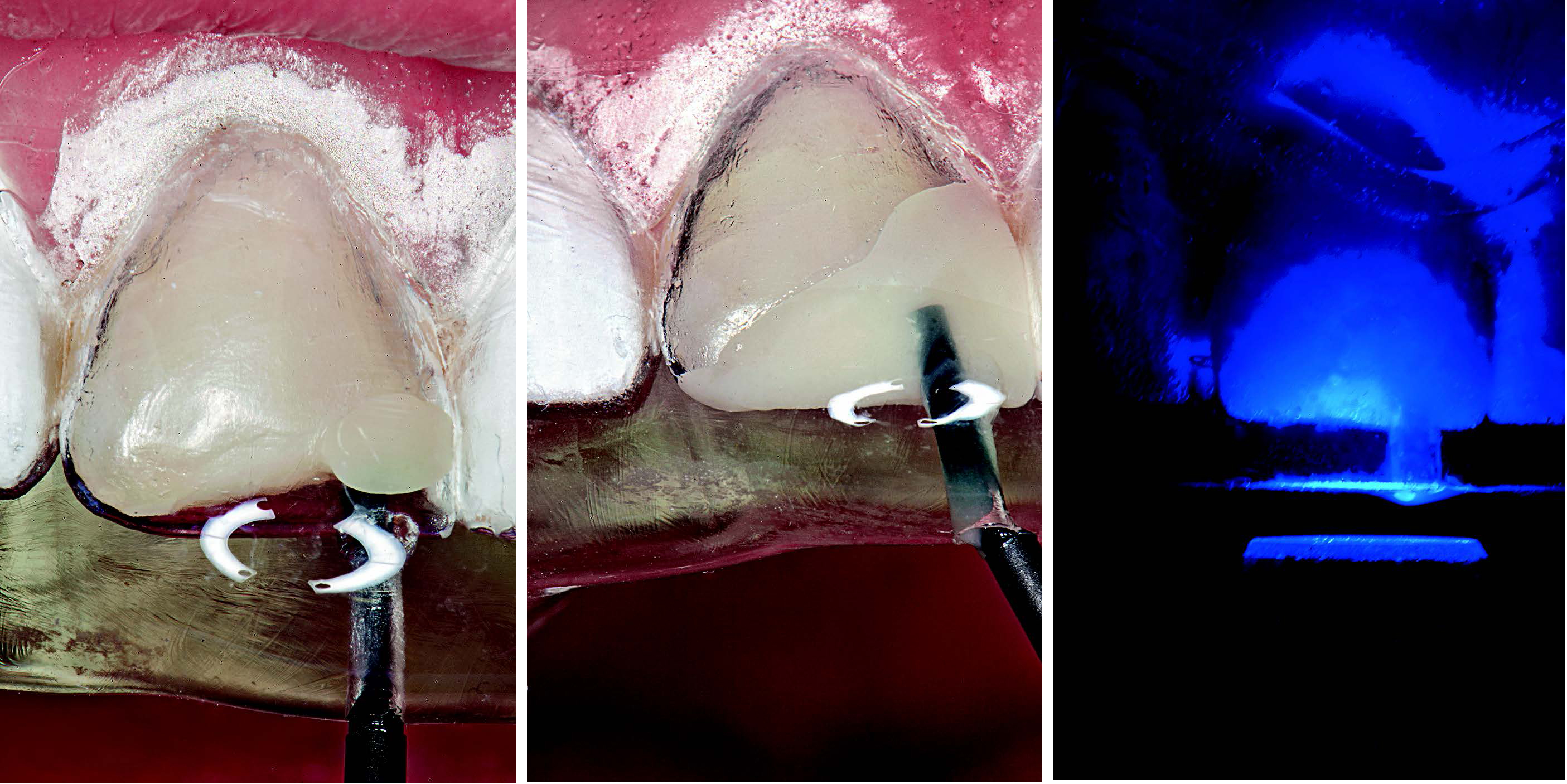

A clear PVS matrix (Exaclear, GC America) was fabricated to replicate the diagnostic wax-up using a nonperforated tray. A small opening was made above each tooth that was to be restored using a tapered diamond bur (6847, Brasseler USA).

The clear silicone matrix was placed over the anterior segment of the maxillary arch, and an opacious A2-shaded flowable resin composite (G-aenial Universal Flo) was initially injected through a small opening above each tooth. An A1-shaded flowable resin composite was then injected to mix with the A2-shaded composite (inverse injection layering technique). The resin composite was cured through the clear resin matrix on the incisal, facial, and lingual aspects for 40 seconds.

The completed resin composite restorations with optimal anatomical form and color integration. The composite restorations establish the optimal esthetic parameters for a natural smile.

One dentist who is already making use of the new formulations is Dr Douglas A. Terry of Houston, Texas. In his new book, Restoring with Flowables, he describes the many clinical uses of flowables and the science behind their success, and he also presents guidelines and case reports for specific applications. To him, the decision to use flowables in clinical situations where others may choose ceramic veneers or crowns is all about the patient. Flowables are a much more affordable option for many patients than ceramics, and they also drastically reduce the treatment time. “I’m like most people,” he says, “and if some doctor tells me it’s going to be $10,000 to get my mouth done, I’m going to think, ‘Well, can we make this in payments for the next 10 years?’ I think these techniques are great because everyone can get it, and esthetics is something that needs to be given. A lot of people can’t have 10 crowns done next week, but does that mean they don’t deserve anything?”

It is not a bad thing for clinicians to defer to the options they personally know will achieve successful results for their patients. However, Dr Markus B. Blatz has said that “the incredible breadth of clinical applications of modern flowable composites, especially in combination with a novel injection technique . . . calls into question the validity of many ‘traditional’ treatment concepts and materials.” So what will it take for more clinicians to give the new generation of flowables a chance?

In some cases, the reluctance to try flowables before ceramics could be a costly mistake. Dr Terry describes a patient who came to him last year with two peg laterals who had seen seven different cosmetic dentists to solve the problem: “First, they did a composite veneer, and it fell off. Then they did a composite ceramic veneer, but it didn’t work. Then they prepared it for a crown, but they exposed a nerve and had to do a root canal. Then she lost her papilla from that procedure and had to have periodontal surgery. After that, she saw another doctor because there was space between the teeth, so they added to the other tooth and they messed up that tooth. So she came to me after seven doctors, and she had spent a fortune. If she had come to me first, I could have had it done in 45 minutes and she would have been out the door, done.”

Preoperative views of the maxillary and mandibular anterior segment. The 11-year-old patient presented for orthodontic and restorative evaluation with a tooth size discrepancy on the maxillary anterior segment with caries present on the proximal surfaces of the maxillary lateral incisors.

The completed resin composite restorations with optimal anatomical form for an 11-year-old. The composite injection technique allowed the establishment of harmonious proportions of the transitional restorations and the surrounding biologic framework. Management of tooth size discrepancies in the preorthodontic treatment-planning stages can be accomplished using this simplified technique with an improved next-generation flowable resin composite.

A 7-year follow-up of the composite transitional restorations after orthodontic treatment was completed. Note the minimal wear.

“I’m not saying that this is a cure-all for all your needs,” Dr Terry continued. “I’m trying to give parameters and ideas of how to use these concepts so you can do more and utilize your imagination. Whether it’s for a prototype or a final restoration, you have to utilize good clinical judgment and experience. You can utilize these materials and you can still go to ceramics afterward if you want. But what do you have to lose?”

As with any new biomaterial, research must be done to fully measure and evaluate the capabilities of flowable composite resins. However, recent studies and clinical experience so far indicate there is a bright future ahead for flowables as they etch their place in modern esthetic dentistry. For more information on the clinical applications of flowable composite resins, please refer to Dr Terry’s forthcoming book, Restoring with Flowables.

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: November | Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: December | Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: January | Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: March | Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: April | Quintessence Publishing Blog