When Martin Chin, DDS, had his first encounter with Crouzon syndrome, he was a 21-year-old dental student spending his free time in Dr Egil Harvold’s craniofacial anomalies clinic. That first encounter sparked a journey of discovery and innovation that would change the face of dentistry.

“A young child, maybe 3 years old, was brought in by his father,” Dr Chin recalls. “The child’s eyes protruded and he was having trouble breathing. Dr Harvold confirmed the child had Crouzon syndrome and explained this to the father. The father responded by saying he didn’t understand our concern. ‘All of my children look like that,’ he said. I went out into the waiting area. Sure enough, there were four children sitting out there, all with Crouzon faces.”

Photos of people affected by Crouzon syndrome from the Children’s Craniofacial Association.

Crouzon syndrome is a genetic disorder that affects the first pharyngeal arch during fetal development. In a person with Crouzon syndrome, the skull and facial bones fuse early, preventing normal bone growth. Because of this, the midface of a Crouzon patient remains much smaller than average during development. The face does not extend outward. Organs such as the eyes and airway are severely compressed, complications which only become more pronounced as the child continues to outgrow his or her disordered bone structure. Severe breathing issues such as sleep apnea can develop, requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines or even tracheostomies. Children with less drastic physical symptoms still suffer emotional effects due to discrimination and abuse from their peers.

When Dr Chin began learning about Crouzon syndrome, most oral and maxillofacial surgeons treating these patients were performing the intracranial monobloc procedure as developed by Dr Paul Tessier. (The modern evolution of Dr Tessier’s procedure is the Monobloc Frontofacial Advancement procedure, which is still commonly performed today on Crouzon patients.) Unfortunately, due to the young age of most patients at the time they required surgery, the limitations of pediatric anesthesia, and the inherent trauma of the operation, the operation had only a 50% success rate.

“The operation is done through what’s called a coronal flap,” Dr Chin explains. “You make an incision at the top of the head, almost like a headband, and you peel the forehead down. The problem is that these children do not have normal skulls. When you’re reflecting this flap down, the brain is often exposed in small areas. You have to separate the forehead tissue from the dura. Each time you do this procedure you increase the chance of directly damaging the brain with your instruments or exposing the brain to infection.

“When I was a student, Dr Tessier came to our hospital to demonstrate the monobloc surgery. They took four children to surgery. Two died during the surgery and two lived. These were high-risk surgeries, but these children and parents were desperate.”

The Start of a New Paradigm

According to Dr Chin, the idea of coming upon major scientific discoveries by accident doesn’t work. We’ve all heard the story of Alexander Fleming’s accidental discovery of penicillin. But Dr Chin stresses that when you are confronted with a problem that is impossible to treat, there is a logical way to approach it.

“Carefully analyze the problem and then determine which technologies can be used in this situation,” he advises. “Those technologies will almost always have to be taken from another medical specialty and adapted. You must be willing to look to another type of doctor or scientist and adapt their technology to your problem. After you do that, you have to figure out how to use it to solve your problem.”

The problem was Crouzon syndrome—a skull too small, a skull that couldn’t grow. The problem was a surgery that gave some children a chance at life but also left far too many dead.

Years after meeting those first five siblings with Crouzon, Dr Chin had a realization while performing a Le Fort III with internal fixation on a young girl with a severe form of Crouzon called klebatschaldel (German for cloverleaf head). As he and the lead surgeon placed the plates and screws that would hold her puzzle of a skull in place, Dr Chin realized something. “Do you know that this is not working?” he asked. The lead surgeon said, “Of course it’s working.”

What Dr Chin had discovered is that the procedure was not actually achieving any length of expansion. Previously, postoperative radiographs were not taken, so he began taking cephalometric radiographs before and after the surgery and discovered that there were no benefits. These traumatic, high-risk surgeries were actually not working.

“At best,” Dr Chin explains, “you could only achieve about a 20% correction with conventional surgery, which means you either have to repeat the procedure multiple times or settle for less. In some cases, when I looked back at what other people had done—they actually got 0%. You could take the radiographs from before and after and they were exactly the same. Twelve hours of surgery—no treatment. If you were aggressive and good at it, you could maybe get 6 mm of movement. But most patients require anywhere from 15 to 30 mm to correct the eye sockets and midface to adult-sized levels so you don’t have to go back later and reoperate. And the mortality rate goes up with each repeated surgery.”

An Ilizarov apparatus treating a fractured tibia and fibula.

But if conventional surgery wasn’t working, how could he get those 15 to 30 mm? And how much could he gain in a single operation? Dr Chin thought back to a lecture he’d attended as a dental student from a Ukranian doctor who had studied under the orthopedic surgeon Gavriil Ilizarov before escaping from the Soviet Union. He had brought several patient records from the hospital in Kurgan where Ilizarov developed his famous bone-lengthening procedure. The procedure uses an external device to slowly distract, or pull apart, two pieces of severed bone in order to lengthen them through osteogenesis. In a way, the theories were similar: Crouzon patients needed a skull that was “longer,” or deeper.

Le Fort III Advancement with Gradual Distraction Using Internal Devices

Around the time Dr Chin was rethinking the conventional surgical protocol, he met a 6-year-old patient whose radiographs before and after the 12-hour surgery showed no advancement. Her mother asked Dr Chin if he had any ideas.

With the concept of Ilizarov distraction in mind, Dr Chin set to work. He designed an internal distraction device that would push the osteotomy segments outward. “There were a number of deaths that were related just to the instruments themselves,” he explains. “Most surgeons are pretty detailed about how they killed the patient, so I had a lot of information on how you shouldn’t do these operations. I then designed the distraction procedure to try to get around where the catastrophic events were occurring.”

The Chin Midface distraction device.

Dr Chin at his personal Bridgeport milling machine.

But when he started looking for a manufacturer to make the device, everyone turned him down. Without evidence of it working, the device was too dangerous to make—the liability to the manufacturers was too much. So Dr Chin asked the manufacturers how they would make the implants, and they told him. He asked them to sell him a Bridgeport mill and send it to his house along with a book on how to use it, and they sent both. Then he manufactured the distraction device and specialty implants himself.

“It’s not normal,” he says, laughing. “When my office would set up these procedures, they would schedule 40 hours outside of the office for me to stand at the milling machine in my garage grinding the titanium implants for a single child.”

Compared with the 50% mortality rate of Dr Tessier’s early procedure, the operation Dr Chin designed has only a 3% to 5% mortality rate. “But still, to have 1 in 25 patients die is upsetting,” Dr Chin says. “Personally, I have never lost a patient on the table ever. We have not lost a single patient on the table to this procedure. We are very careful. I designed the procedure to minimize risk.”

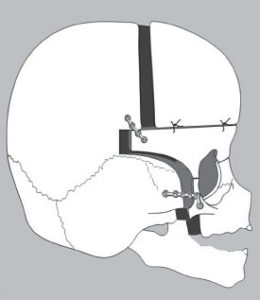

Diagram of the Chin Midface device in the bone structure of a patient undergoing a modified Le Fort III osteotomy with midface advancement to treat midfacial hypoplasia caused by prior radiation treatment for pharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma. The surgery is designed to open three bone-forming chambers. Point A is the pterygomaxillary junction, point B is the divided molar bone, and point C is the nasal aperture and orbital floor. The bone-forming chambers fill with structural bone without the benefit of grafting or growth factors.

The patient’s appearance before Le Fort III midfacial advancement and 1 year afterward.

An Unavoidable Risk

There is another risk that Dr Chin has learned to prioritize.

“When you work on children with craniofacial deformities, there is a sort of evolution as the child ages,” Dr Chin explains. “When the child is very young, it’s actually engaging to have everyone in the room come and look at them. They feel special. But then they get a little older and realize, ‘They’re looking at me because I look funny.’ Once the child’s peers and other people around them start to make comments, the child generates this idea that they’re not whole, they’re not okay, they’re not good. What you never want to do with a child is give them this idea that they’re so ugly they need to have an operation—that doesn’t do their mental health any good. You never want to tell the child that you’re going to make them beautiful. My patients ask me, ‘When you’re done, will I be beautiful?’ And I tell them, ‘The only thing I can guarantee you is that you’ll be different.'”

In an opinion piece for The New York Times, Ariel Henley writes about this aspect of Crouzon: the hidden effects, both from the disfigurement and from the treatment. Dr Chin performed his surgery on Ariel and her twin sister twice, once when they were 6 years old and again at 12 years old. “Even with the physically traumatic surgeries I was required to undergo,” she writes, “the physical aspect of my condition was nothing compared with the emotional toll of living with an appearance-altering condition. The everyday stares, comments, and subhuman treatment acted as a constant reminder of my painful medical history and my perceived shortcomings.”

Ariel Henley, radiographs and facial appearance before Le Fort III midfacial advancement with distraction and 14 days afterward. The midface-mobilizing device was used to mobilize the maxilla at the Le Fort III level along with the zygoma, inferior orbits, and nose. Internal distraction devices were used to transport the midface anteriorly, opening a 20-mm pterygomaxillary bone-forming chamber. The anterior fragment contained developing teeth that supply neuromuscular signaling to the bone-forming chamber. The pterygoid muscles attached to the intact pterygoid plates supplied neuromuscular signaling from the posterior aspect of the chamber. No bone grafting was necessary.

She continues: “Because salvaging my physical health was so crucial, the emotional aspect of living with a facial disfigurement was overlooked by health professionals. While my mother and father did their best to offer support, there was only so much they could do. I tried therapy, but therapists always seemed to ask the wrong questions and never seemed to understand what it was like to have my physical appearance change drastically time and time again. ‘It’s like in Freaky Friday,’ I would tell them. ‘Except I never get my body back. I never get my face back.’ Despite their best efforts, they simply could not relate.”

Dr Chin used to send all of his patients to a psychotherapist—a former patient who had undergone the surgery herself and was uniquely positioned to understand exactly what current patients were going through. After she relocated, Dr Chin began counseling patients himself. “I usually study my patients for 1 to 2 years before undertaking the surgery,” he explains. “In that time I am going to understand what you think so I will not disappoint you. Then I follow patients forever afterward.

“These patients require time to assimilate to their new appearances. With good support, they are usually fine. But I’ve also made mistakes, and the mistakes that I’ve made were devastating.” Dr Chin recalls a time when he missed a patient’s severe depression and ended up with a death. “After the patient left the hospital, they didn’t come back for the postoperative exam. At all. Their postoperative appointment was for 3 weeks later, but in the mean time they hung themself. A child.”

Putting the Patient First

When you grow up with a frequently changing face and a standing reservation in the operating room, a lot can feel out of your control. Dr Chin confronts this by giving his patients as much control as he can. In his appointments the parents sit behind the child, and he speaks directly to the child:

“I often ask, ‘Well, what do you think?’ And they say, ‘Well, I think my face looks pushed in. I don’t like it.’ And I say, ‘Well I can do an operation that can make this look more like this.’ And the patient will say, ‘Oh yeah, I would like that, I think.’ You don’t ever want to imply that the child is not okay the way they are. That impression doesn’t go away, even if you correct the problem. They still feel defective.”

Ariel agrees. “One thing I appreciated about Dr Chin was his willingness to be honest and straightforward with me,” she recalls. “He did a great job of working with my parents to help me feel like I always had a say in what was done. I can still remember sitting in my hospital bed waiting to go in for surgery and having Dr Chin go over the details with me. He would describe what he was going to do and how he was going to do it. Allowing me to be part of the process gave me a sense of control that I desperately needed.”

Ariel has a unique perspective on the emotional toll of Crouzon treatment. “I didn’t experience these surgeries and recovery periods alone,” she says. “I witnessed my twin sister go through them, too. This is part of the reason why I’m so vocal about my experiences, because I know what it’s like both as a patient and as a witness. It’s hard to make sense of these experiences, but trying to process my own situation while watching my sister—someone I love more than life—recover from such major operations as well was often traumatic.”

Continuing to Advance

In her piece for The New York Times, Ariel stresses the emotional toll both of living with facial disfigurement and of treatment and recovery. “Since my article came out a few months ago,” she says, “I’ve received dozens of emails from doctors and surgeons all over the country telling me they’ve only recently begun paying attention to the mental and emotional effects of procedures on patients. Some even apologized for not realizing sooner. I think this is an excellent step in the right direction—it’s important for surgeons to recognize the importance of treating the whole patient. If mental health can be addressed by specialists, I think physical and emotional recovery will be less traumatic. I strongly believe counseling and therapy should be required both prior to and after surgery. Almost every single adult I’ve met with Crouzon syndrome has at one point struggled with depression and/or PTSD symptoms. Many didn’t seek professional help until they reached adulthood and then had trouble finding a specialist who understood the struggles they faced.”

She offers a framework for professionals to improve: “Hospitals with craniofacial departments should offer support groups for patients to meet other individuals with similar experiences and connect current patients with previous patients to establish a mentor/mentee relationship. I also think all craniofacial surgeons should be required to sit in on a panel of previous and current patients to learn about the patient perspective. I believe this should happen once per year as part of ongoing training. Consulting with patients to understand the patient side of the condition will allow for greater empathy and well-rounded care. Many patients feel isolated in their experiences: Connecting them with a person or a group of individuals who have had similar experiences can help them feel less alone.

“The surgeries I had as a child changed my life. These procedures allowed me to live a rich and normal life. They boosted my self-confidence and improved my quality of life. This is an easier conclusion to reach now that I’m an adult—now that I’m no longer in the depth of recovery. During recovery, I had a hard time understanding the benefits because all I could focus on was the physical and emotional pain. These procedures were hard. They were really, really hard. They were excruciating—physically and emotionally.”

An illustration of the osteotomy Dr Chin performed on Ariel Henley showing the segment of her skull that was separated and then projected outward by the midfacial advancement distraction.

Her final piece of advice? “For surgeons performing these procedures and treating individuals with Crouzon or other craniofacial disorders, I would say be present. Treat each patient and each family as if they are your own. This always made me feel safe and allowed me to worry less about the procedure and more about healing and feeling better.”

As for Dr Chin, he continues to search for unconventional surgical solutions to oral and maxillofacial surgery’s most challenging problems. His book, Surgical Design for Dental Reconstruction with Implants: A New Paradigm (Quintessence, 2015), offers solutions for cases where conventional surgery has failed. Cases described in the text include using Sharpey’s fibers from the periodontal ligaments of developing teeth to generate bone in deficient areas, substituting bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) when conventional bone grafting is likely to fail, and combining osteotomies with distraction principles and the body’s own generative processes to fill congenital defect regions such as cleft palates without bone grafting. Like his revolutionary Crouzon surgery, the procedures have been designed to minimize trauma and risk to the patient by working around the events where conventional surgery would fail. More importantly, these advanced concepts can be applied to routine surgeries to avoid complications, increase reliability of results, and streamline the use of costly materials such as BMP or growth factors by “hacking” the biologic processes at the cellular level.

Some would say all of this happened by chance. But if the image of Dr Chin spending hours on end milling custom titanium implants for his patients and the writings of Ariel on facial equality and patient-centered health care say anything, it’s that change can only occur when determination to alter the current paradigm exists.

Martin Chin, DDS, is an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who maintains a private practice at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. His private practice focuses on orthognathic, craniofacial, and dental implant surgery. He is also an attending surgeon at the University of California Children’s Hospital in Oakland. Dr Chin has developed many devices and techniques for distraction osteogenesis of the orbit, midface, and alveolar processes. Multiple US and international patents have been issued for these innovations, and Dr Chin has written and lectured internationally on these topics. He maintains an active research program for the development of instruments and processes to improve the practice of maxillofacial surgery. He is also the founder and director of the Beyond Faces Foundation, which supports treatment of children with craniofacial disorders. Dr Chin is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and a fellow of the American College of Dentists. His book, Surgical Design for Dental Reconstruction with Implants: A New Paradigm, bridges the gap between the routine practice of maxillofacial surgery and theoretical laboratory science to establish a working model that can be applied to real problems affecting real patients.

Martin Chin, DDS, is an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who maintains a private practice at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. His private practice focuses on orthognathic, craniofacial, and dental implant surgery. He is also an attending surgeon at the University of California Children’s Hospital in Oakland. Dr Chin has developed many devices and techniques for distraction osteogenesis of the orbit, midface, and alveolar processes. Multiple US and international patents have been issued for these innovations, and Dr Chin has written and lectured internationally on these topics. He maintains an active research program for the development of instruments and processes to improve the practice of maxillofacial surgery. He is also the founder and director of the Beyond Faces Foundation, which supports treatment of children with craniofacial disorders. Dr Chin is a diplomate of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and a fellow of the American College of Dentists. His book, Surgical Design for Dental Reconstruction with Implants: A New Paradigm, bridges the gap between the routine practice of maxillofacial surgery and theoretical laboratory science to establish a working model that can be applied to real problems affecting real patients.

Ariel Henley, is a writer with a bachelor’s degree in English and political science from the University of Vermont. She is passionate about writing as a form of activism. Much of her work explores her experiences growing up with a facial disfigurement as a result of Crouzon syndrome. Ms Henley writes to explore issues related to beauty, equality, human connection, and understanding trauma through the lens of her own experiences. She shares her story in an effort to help eliminate stigma, educate others about the importance of facial equality, and promote mainstream inclusion for individuals with physical differences. Ms Henley’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vice, The Rumpus, and Narratively. She is a 2017 San Francisco Writers’ Grotto Fellow and is currently working on a memoir.

Ariel Henley, is a writer with a bachelor’s degree in English and political science from the University of Vermont. She is passionate about writing as a form of activism. Much of her work explores her experiences growing up with a facial disfigurement as a result of Crouzon syndrome. Ms Henley writes to explore issues related to beauty, equality, human connection, and understanding trauma through the lens of her own experiences. She shares her story in an effort to help eliminate stigma, educate others about the importance of facial equality, and promote mainstream inclusion for individuals with physical differences. Ms Henley’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vice, The Rumpus, and Narratively. She is a 2017 San Francisco Writers’ Grotto Fellow and is currently working on a memoir.

1 Response to How One Surgeon Changed the Lives of Patients with Crouzon Syndrome Worldwide