The human body is a complex physical structure, capable of macro feats like walking in a stable, upright position and micro feats like writing or handling surgical instruments. And just like the frames of buildings—from small houses to looming skyscrapers—the architectural frame of our body influences the appearance and character of everything that is laid over it. Nowhere in the human body is this more apparent than in the face, which serves as the physical ambassador of our thoughts, our emotions, and our identities to the world around us. While the external soft tissue provides the details, the internal bony frame provides the character of the face through projections and contours of the skeleton and the symmetry of the presentation. So how do you restore that character after the bones of the face have been damaged by trauma?

Identifying the Pieces of the Puzzle

Before you can begin to conceptualize how to put a face back together, you must first understand how it functions when whole.

“When attempting to understand facial fractures and their effect on appearance and function,” explains Yoh Sawatari, DDS, author of the new book Surgical Management of Maxillofacial Fractures, “the surgeon must begin by compartmentalizing the face and defining the character of the bones. The facial skeleton may be divided into three different regions: the frontal region, the midface, and the mandible. The facial bones can be further conceptualized and defined into two different types of architectural structures: dense rigid buttresses and laminar sheets. The buttresses are traditionally dense cortical pillars that provide stability and structure to the face. They are responsible for the contours and dimensions of the face as well as the support for the laminar bone and the entire soft tissue component of the face enveloping the facial skeleton.”

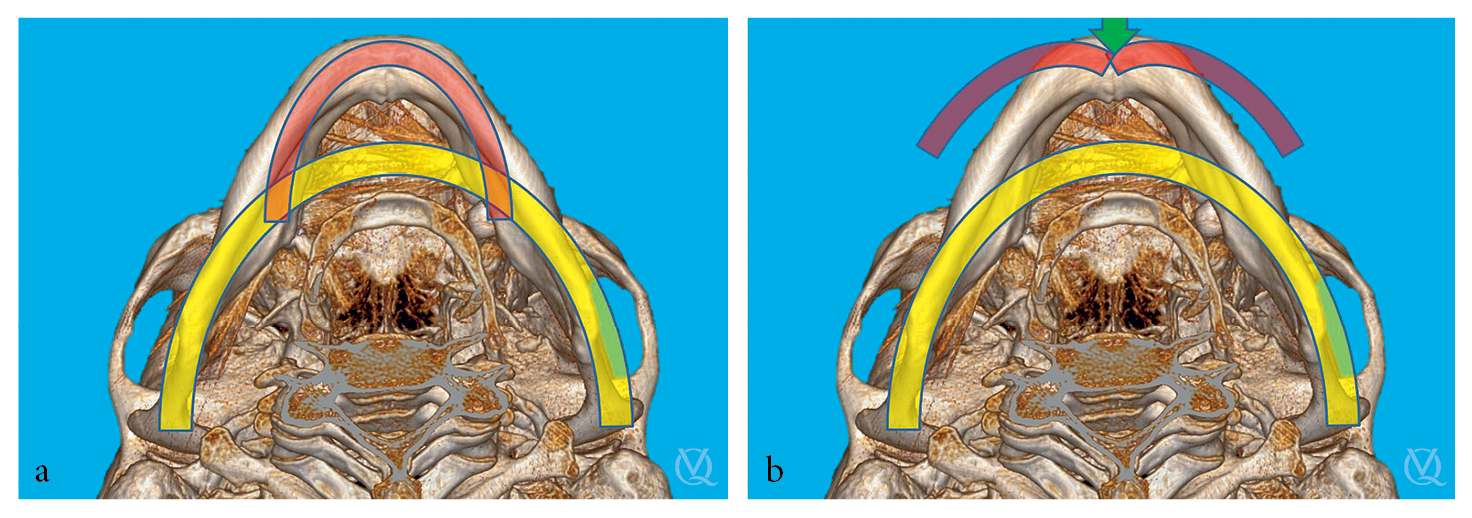

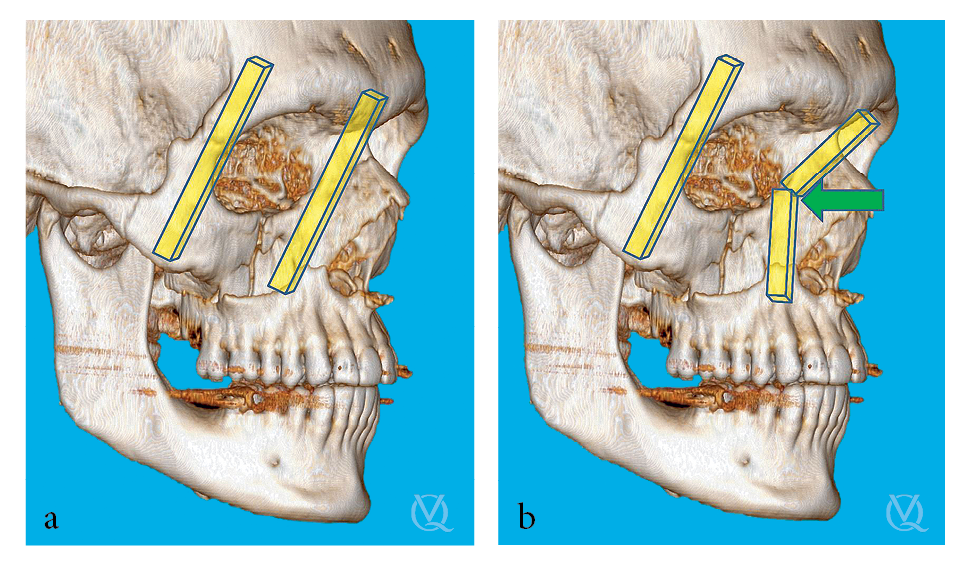

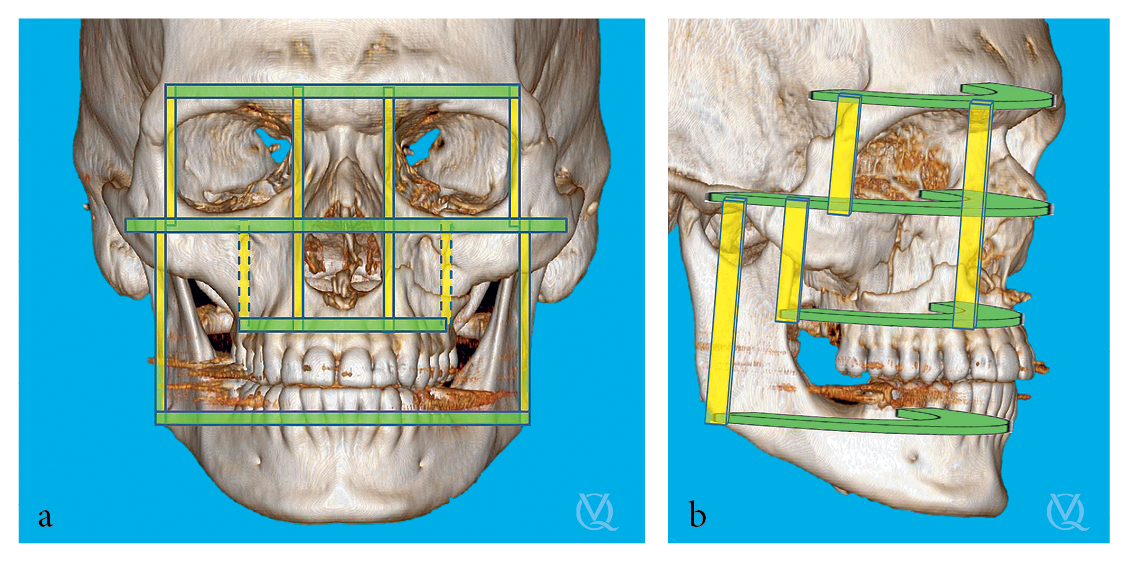

The buttresses of the face are further divided into horizontal and vertical buttresses. Horizontal buttresses are characterized by dense bone and have an arcuate shape. From top to bottom, the four horizontal buttresses include (1) the supraorbital bar; (2) a bar at the infraorbital rims and zygomatic arches; (3) another comprising the cortex from the pterygoid plate to the floor of the nose across to the contralateral pterygoid plate; and (4) the inferior aspect of the mandible. The vertical buttresses are also comprised of dense cortical bone, but they occur in four pairs of columnar formations. The first pair of vertical buttresses occurs at the bilateral nasofrontal section extending along the piriform rim, the second at the zygomaticofrontal junction, the third at the pterygoid plates, and the final pair at the ramus of the mandible. Areas where the vertical and horizontal buttresses intersect with each other include at the maxillary buttress, the base of the piriform aperture, the nasofrontal junction, and the angle of the mandible.

“To understand fracture patterns,” Dr Sawatari explains, “it is important to understand the concept of these vertical and horizontal buttresses and the intersections they create. Based on the distribution of forces, the horizontal and vertical buttresses fracture in different ways. Because the majority of facial fractures develop from the application of force from an anterior-to-posterior vector, the way in which the facial bones fracture is somewhat predictable. When force is applied to the horizontal buttresses, due to the arcuate shape, the bone fractures with displacement of the anterior segment posteriorly (losing projection), and the posterior segments splay in a lateral dimension. On the other hand, when vertical buttresses fracture, the central section of the buttress also displaces in a posterior vector, and the vertical height is shortened. Understanding the differences between how these buttresses fracture allows the surgeon to understand the resultant deformities that are created from these facial fractures. The loss of projection of a naso-orbitoethmoidal (NOE), Le Fort, or zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fracture is due to fracture of a vertical buttress. On the other hand, the development of telecanthus, the widening of the zygomatic arch, and the widening of the posterior mandible from a symphysis fracture are due to fractures of a horizontal buttress.”

(a) All horizontal buttresses are arcs. (b) Force application to a horizontal buttress leads to decreased anterior projection and increased posterior transverse width.

(a) All vertical buttresses are struts. (b) Force application to a vertical buttress leads to decreased anterior projection and decreased vertical height.

The organization of Dr Sawatari’s book is based on these fracture patterns so that when surgeons are presented with a facial fracture, they can easily reference that specific chapter to review the knowledge necessary to appropriately manage that fracture.

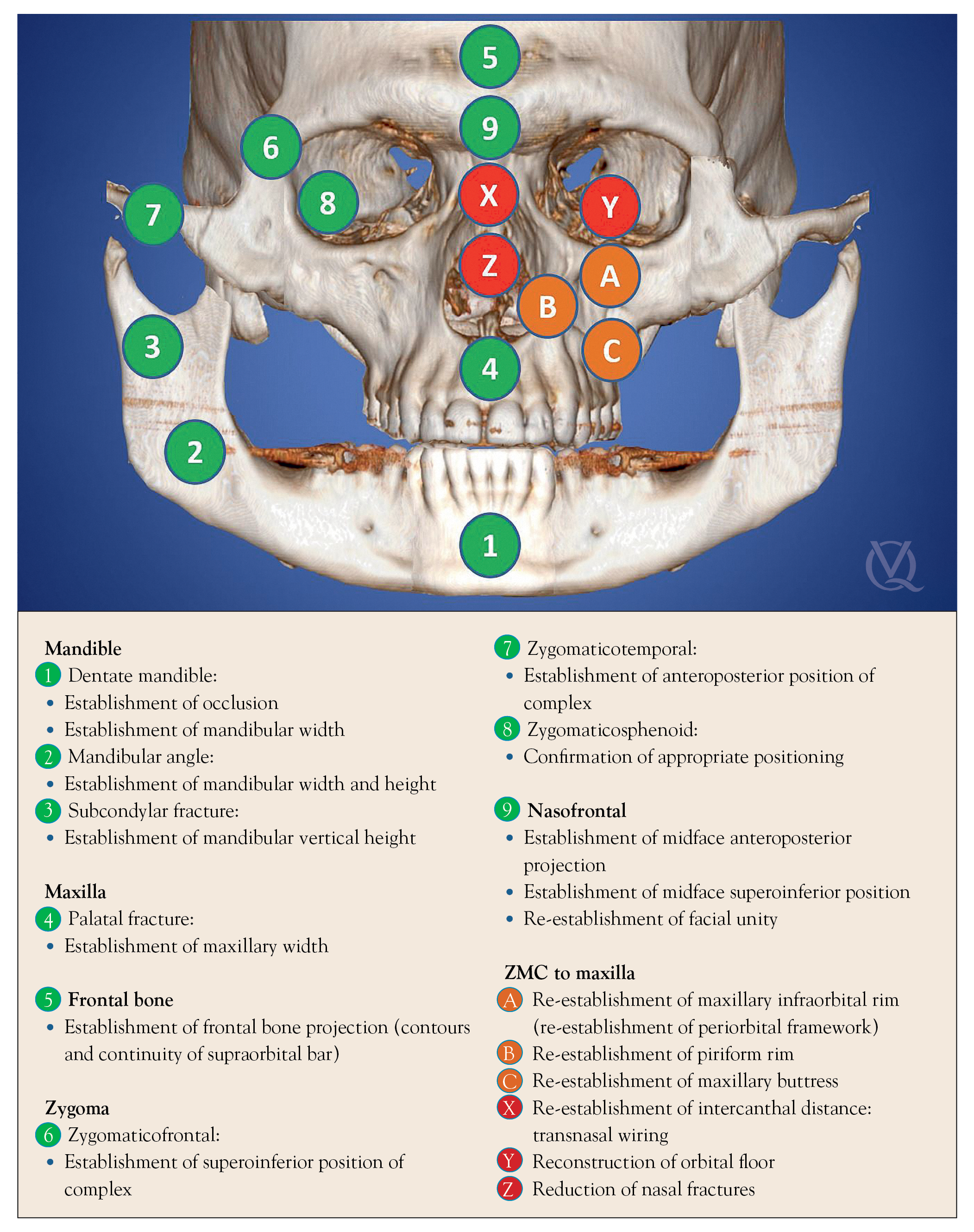

“In order to effectively manage facial fractures,” he continues, “the objective is to reverse the damage that the buttresses sustained and restore appropriate facial dimensions. This translates to the uprighting of the vertical buttresses, the reduction of the posterior horizontal buttresses, and the restoration of anterior projection for both vertical and horizontal buttresses. Thus, generally all fractures of the face will require restoration of the anterior projection, restoration of the vertical height, and closure of the widened posterior dimensions of the face. The management of each fracture type is ultimately dependent on the location of the fracture, and the concept of fracture management is always the same: Use adjacent stable bone as a reference and bring unstable fractured segments to the stable references; this is reduction. Once the fractured segments are aligned and the preinjury position is established, fixation is used to stabilize the fracture to prevent collapse of the segments and allow for appropriate bony apposition for immobility and adequate healing. The stable references are invariably the vertical and horizontal buttresses of the face, and the fixation points for all facial fractures are traditionally the intersection of the vertical and horizontal buttresses.”

Once the structural basis of the face is understood, the concepts of traumatic injury can be applied to further predict the fracture patterns of the face, giving the surgeon a sense of what lies beneath before imaging confirms.

“Essentially all facial fractures are a combination of vertical and horizontal buttress fractures,” Dr Sawatari explains. “However, there are multiple factors that influence the incidence of each type. The first factor that determines the incidence of fractures is the location of the face that is struck, because any area of the face that projects more tends to be more susceptible to fracture. The nose is first, followed by the ZMC, and then the mandible. The second factor that dictates the incidence of fractures is the mechanism. The most common cause of facial fractures is assault, followed by falling and motor vehicle crashes. The third factor that influences fracture type is the amount of force applied to the face. The classic laws of physics are always at work when analyzing facial fractures. An assault by a fist is far different from an assault with a solid object, which is again very different from the force of a high-velocity motor vehicle crash to the face. The greater the force, the greater the damage inflicted, and the more fractures, the more comminution that the patient will likely develop from the injury.”

Understanding how the face breaks is far easier than having to put those pieces back together. Structural damage to important components of the frames of buildings or cars can compromise the entire unit by affecting the stability of the unit as a whole, and the face is no different. The responsibility of the maxillofacial surgeon lies in restoring stability to the facial unit by rebuilding each small piece, section by section, brick by brick, until the stability of the face as a whole has been restored.

Putting the Pieces Back Together

When facial fractures are reduced and fixated appropriately, both function and form are restored.

Bring unstable fragments to stable bony references and rebuild. Find a place to start, treat that area, then move on to the next.

“A case with multiple fractures is more difficult and time-consuming than a single fracture,” Dr Sawatari explains, “because there is greater variability in the positioning of the fractured segments. This increased variability requires greater exposure of bone and more attention to sequencing, and it presents an increased possibility of inaccuracy. The management of facial fractures is never straightforward or easy. However, the basic concept remains the same: Bring unstable fragments to stable bony references and rebuild.”

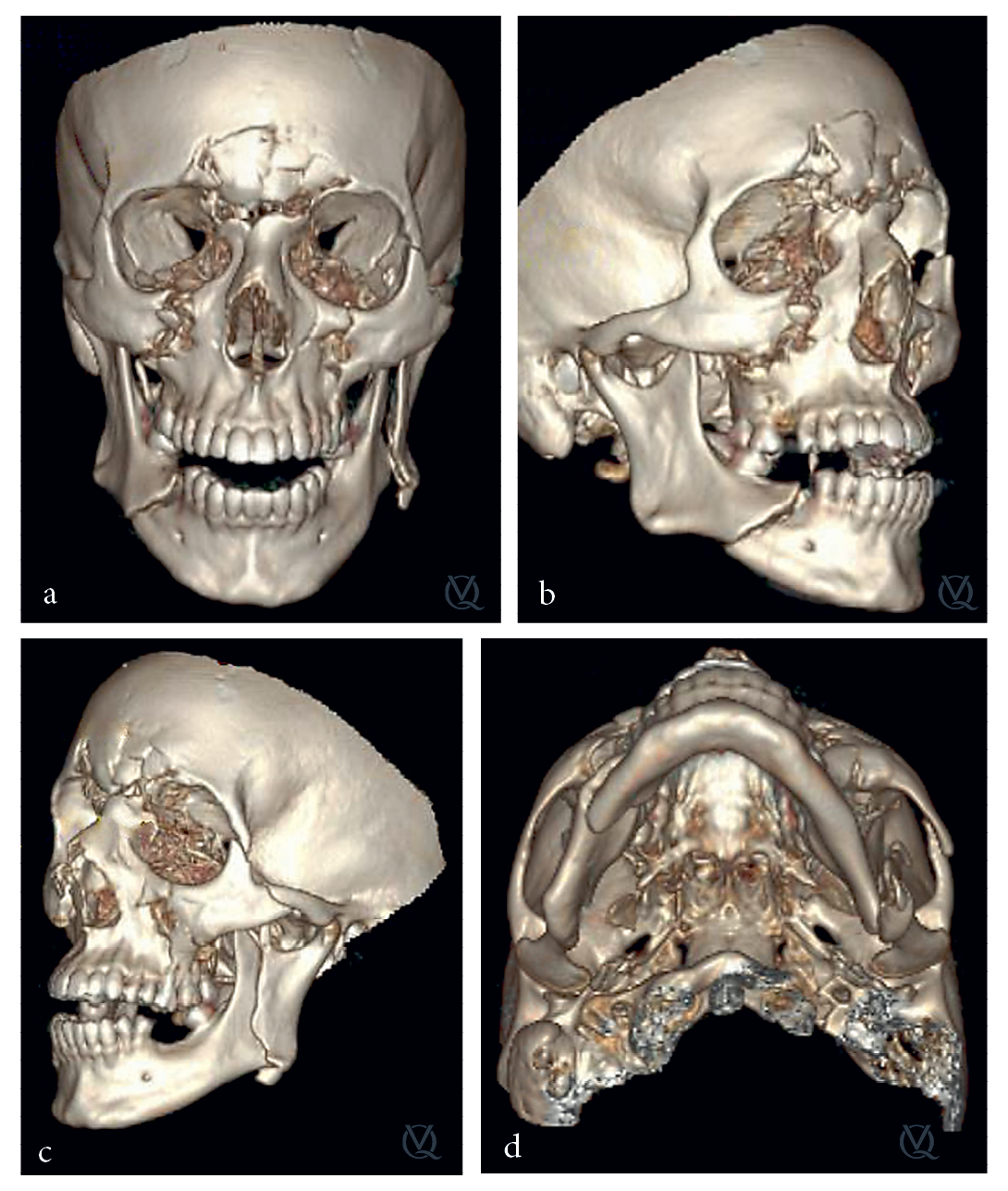

“One of my most memorable cases involved a young man who sustained severe facial fractures from an industrial accident with a pipe exploding into his face,” Dr Sawatari recalls. “He presented with severe soft tissue injuries, but he had also sustained multiple facial fractures involving both the mandible and zygoma. In this complex case, time was spent on first collecting data. After a thorough clinical examination was completed, we reviewed the CT scan at length. Axial and coronal cuts were reviewed, and the 3D reconstruction was thoroughly analyzed. We then developed a plan. The data established that the patient had a left subcondylar mandible fracture and a severely displaced and comminuted left orbito-zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture. Due to the severe comminution and displacement of the fractures, we determined that we would need to perform multiple surgical approaches to expose reliable stable points of reference. We then formulated a logical sequence of procedures based on the need to reestablish specific dimensions of the complex. The procedure was then executed based on the established plan. Although it was difficult, the procedure proceeded without any unexpected complexities. By thoroughly evaluating the patient and CT scan prior to the surgery, establishing stable reference points, evaluating the complexity of the case, identifying access incisions to be used, and sequencing the reduction/fixation, the management was efficient and resulted in an effective surgical outcome. This case was memorable due to the patient’s satisfaction and appreciation. The patient’s spirits were so positive even after sustaining such a severe, deforming traumatic injury. With successful evaluation and planning, we were able to execute a surgical treatment plan that resulted in an ideal functional and cosmetic outcome. The combination of the patient’s gracious personality and the successful outcome resulted in one of the most gratifying cases in my career.”

(a and c) Preoperative clinical presentation and 3D reconstruction. (b and d) Postoperative clinical presentation and 3D reconstruction.

In Surgical Management of Maxillofacial Fractures, Dr Sawatari facilitates the achievement of successful outcomes by compartmentalizing the face. By breaking the face down into smaller regions and addressing each fracture thoroughly—from clinical evaluation and treatment planning to surgical execution and postoperative assessment, start to finish—he makes the complex manageable. The logical sequencing necessary for facial fracture management is reflected in the logical sequencing of the book, making it a valuable and accessible reference for surgeons actively managing facial fractures. The structure of the book, as well as the writing, brings a necessary sense of order to an inherently chaotic event—traumatic injury—and imbues on it the logical sensibility of a surgeon’s thought process.

Yoh Sawatari, DDS After graduating from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry in 1995, Dr Sawatari joined the Public Health Service/Indian Health Service on the Navajo Reservation in Arizona. He worked as a general dentist for 5 years and received numerous commendations and awards and was promoted to Lieutenant Commander. He then completed his postdoctoral residency training in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital Residency program. He then worked in private practice for 2 years before being recruited to return as faculty to the University of Miami, where he is currently an Associate Professor and the Director of Residency of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery program.

Yoh Sawatari, DDS After graduating from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry in 1995, Dr Sawatari joined the Public Health Service/Indian Health Service on the Navajo Reservation in Arizona. He worked as a general dentist for 5 years and received numerous commendations and awards and was promoted to Lieutenant Commander. He then completed his postdoctoral residency training in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Hospital Residency program. He then worked in private practice for 2 years before being recruited to return as faculty to the University of Miami, where he is currently an Associate Professor and the Director of Residency of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery program.

Surgical Management of Maxillofacial Fractures

Surgical Management of Maxillofacial Fractures

Yoh Sawatari

The facial skeleton is comprised of vertical and horizontal buttresses and the intersections they create; maxillofacial fractures occur when these buttresses sustain more force than they can withstand. The objective when managing these fractures is to reverse the damage that these buttresses sustained and restore appropriate facial dimensions. Not all fractures propagate in the same pattern, so surgeons must compartmentalize the face and define the character of the individual bones. This book approaches the face one bone at a time, outlining how to evaluate each type of fracture, the indications for surgery, the surgical management, and any complications. Specific protocols for clinical, radiographic, and CT assessment are included, as well as step-by-step approaches for surgical access and internal reduction and fixation. Isolated fractures are rare with maxillofacial trauma, and the author discusses how to sequence treatment for concomitant fractures to ensure the most successful outcome. This book is a must-have for any surgeon managing maxillofacial fractures.

256 pp; 254 illus; ©2019; ISBN 978-0-86715-794-9 (B7949); US $178

This article was written by Caitlin Davis, Quintessence Publishing.

©2019 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY. NO PART MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER.

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: April | Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: May | Quintessence Publishing Blog