Reading time: 17 minutes

Metal-ceramic restorations have long represented a reliable tooth-replacement option; however, they have begun to fall out of favor as all-ceramics systems have improved by leaps and bounds and patients continue to request tooth-colored restorative materials. As these changes have occurred within the industry, some clinicians are questioning the continued relevance of metal-ceramic technology and whether it is compatible with the current demand for esthetics. But according to prosthodontists W. Patrick Naylor and Charles J. Goodacre and master dental technician Satoshi Sakamoto, esthetics and metal-ceramic restorations can be a perfect fit.

Material Choice: A Generational Shift

Even as the dental industry’s overall preference shifts toward all-ceramic restorations, metal-ceramic restorations still occupy a significant niche within restorative dentistry: posterior restorations. According to a 2016 study on material selection for single-unit crowns, clinicians were almost equally likely to restore a first molar with an all-zirconia restoration as with a metal-ceramic restoration. This study also cautioned that “decisions for crown material may be influenced by factors unrelated to tooth and patient variables” and that clinicians should be cognizant of these factors. Perhaps most strikingly, one of the indirect factors significantly influencing material choice was how recently a clinician had graduated, with newer clinicians preferring all-ceramic over metal-ceramic.

Dr Naylor, author of the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology (Quintessence, 2018), explains this shift: “Once these recent graduates get out of dental school, they get bombarded with literature and advertising promoting these inexpensive all-ceramic materials. Metal-ceramics are still a part of dental education but not the way they used to be. One of the biggest changes is that dental students and even graduate dentists in advanced training programs are receiving less and less technical training in the fabrication process for metal-ceramic restorations. More procedures are given to the laboratory to perform, whereas historically those procedures were taught to and performed by dentists. The theory now is that the clinician does the clinical work, and the laboratory technician does the laboratory work—but unless you’ve gone through the process of fabricating a metal-ceramic restoration, you really don’t have the same depth of knowledge and insight as someone who has. You haven’t seen how the technical work is affected when you underprepare a tooth or don’t provide two-plane reduction, or how the esthetic result is compromised when you only take off one millimeter of tooth structure on the occlusal surface and now can’t create secondary anatomy because there’s no depth. Because of the educational deficits, newer clinicians don’t have that experience in the laboratory that they can call upon in the clinic.”

“And that’s a handicap for them,” Dr Goodacre adds. “If you’ve never made something, you don’t know what someone else is going to need to make it.”

Mr Sakamoto, who works with Dr Goodacre at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry, commiserates: “I work with many dentists who send me impressions, bite records, and shade and facial information. Almost none of them send perfect information. But Dr Goodacre actually knows how to make a crown, so he knows what I need in order to do my job well.”

(left) By any measure, the metal-ceramic restoration on the maxillary left central incisor was not treatment planned properly or executed well clinically. The dental laboratory outcome was also flawed in many respects: shade, length, outline form, surface texture, and level of glaze. Outcomes such as this warrant criticism of metal-ceramic restorations. Take a moment to critique this restoration, and note what changes should be made when replacing this crown. (right) Thanks to retreatment with proper treatment planning, improved execution of clinical procedures, and a high-quality laboratory outcome, the restoration on the maxillary left central incisor now blends well with the adjacent natural tooth. This is a metal-ceramic crown with a porcelain margin. (Courtesy of Dr Charles Goodacre and Mr Satoshi Sakamoto.)

“Most dentists today haven’t made many crowns,” Dr Goodacre emphasizes. “I’m from the old school where we made a lot of them, and I made hundreds for myself in the early years of practicing. Of course, I could never make them look as good as Satoshi does, but I did learn what was important in terms of tooth preparation and the records you need to make. I was shocked when I read a recent JADA article where they went to different laboratories and looked at 1,157 different impressions to determine whether they were adequate or not; 86% of those impressions had at least one detectable error, and 55% of those were critical errors related to the finish line. The impression is a really key portion of the fabrication process because you rely on the impression to get a good fit, and fit is a difficult thing to achieve.”

But with the changing landscape of education and material preference in dentistry, should newer generations even continue with metal-ceramics? Drs Naylor and Goodacre think they should.

“A lot of people have turned to all-ceramics because it’s simpler in some respects and it’s inexpensive compared with metal-ceramics,” Dr Naylor explains. “But if you talk to the people who are doing a lot of high-quality dentistry, they’re still using metal-ceramics.”

“In over 45 years of practice,” Dr Goodacre adds, “I have seen limited complications with metal-ceramic restorations. We have nowhere near that track record so far with all-ceramic systems—we don’t even have 20 years of data yet.”

“In metal-ceramics, we have a number of very high-quality alloys with very predictable behavior,” Dr Naylor says, “and technicians generally have a porcelain system they like to use for each metal alloy and have perfected the application process. And the restorations last for years if not decades. I’m not the only one doing this, and Dr Goodacre and Mr Sakamoto aren’t either. Dr Irena Sailer has some metal-ceramic restorations in Color in Dentistry (Quintessence, 2017). There are a lot of good clinicians doing metal-ceramics and doing them well.”

Drs Naylor and Goodacre stress that neither all-ceramic nor metal-ceramic is perfect for every situation. “The main disadvantage of a metal-ceramic crown is that light doesn’t pass all the way through it,” Dr Goodacre explains. “You have the metal substructure, which you have to block out with opaque porcelain. So all-ceramic has the advantage when you have a tooth that is very thin or translucent. If the color of the dentin is normal, then that color will pass through an all-ceramic crown and give you an optimal esthetic result. But that opaqueness can be an advantage in other situations. If the tooth is discolored, you’ll have a better result with a metal-ceramic crown than you would with all-ceramic because that dark discoloration will show through the all-ceramic.”

In Color in Dentistry, the authors describe a case involving the replacement of two crowns on both the patient’s maxillary central incisors where the left tooth was nonvital and discolored and the right was vital and nondiscolored. Complicating the treatment planning and material selection was the patient’s insistence on all-ceramic restorations rather than metal-ceramic—the two original 20- to 30-year-old metal-ceramic crowns were opaque and not natural-looking, not to mention unsuccessful at masking the cervical discoloration of the tooth root. However, even after placing opaque zirconia frameworks, the technician was not able to fully mask the discolored left central incisor. Luckily, the technician had also made a pair of metal-ceramic crowns that the team compared at try-in, and the patient ended up agreeing with the team that the metal-ceramic crowns were better after all. The metal-ceramic crowns allowed the technician to start with the same gray framework color on both teeth, while also allowing for a thinner framework with a stronger value of opacity and larger ceramic shoulders to better reflect the veneering ceramic. (Case rehabilitation performed in collaboration with Walter Gebhardt, DT.)

“Most clinicians will have a conversation with the patient and explain which material they think is best for each clinical situation,” Dr Naylor says. “The problem is that there are some clinicians who feel all-ceramic is appropriate for every situation. They’ve got the system in their office so they try to adjust their cases to use that material wherever possible. But a good clinician will choose the type of restoration for each patient based on what they feel is appropriate functionally and will also meet the esthetic expectations of the patient. Different patients have different priorities. Material choice is an individual decision that has to be achieved through a very enlightening conversation between the patient and the clinician, and good clinicians will have an armamentarium and select different types of restorations for different patients. It’s complex, and there are no simple answers.”

So how do we maintain this technology? To solve the education dilemma, we don’t necessarily have to turn back the clock on how education curricula have evolved. Expert knowledge of metal-ceramic fabrication still exists, and if clinicians want to reclaim that technical knowledge and make quality metal-ceramic restorations a treatment option for their patients, it’s only a phone call away—to the laboratory technician.

From the Clinic to the Lab: An Important Partnership

A good relationship between the clinician and the laboratory technician can have a profound effect on the esthetic success of a metal-ceramic restoration. Dr Naylor advises that clinicians hoping to elevate the esthetic quality of their metal-ceramic restorations, especially newer clinicians, should forge a collaborative working relationship with laboratory technicians.

“Spend some time with the dental laboratory you use,” he says. “Some clinicians have to mail their work out to laboratories far from their practice if they’re in a rural setting, but there are still tools you can use to facilitate open communication in that situation. Develop a relationship with your dental laboratory. Go there, look at their work, talk to the laboratory technician, and ask what they need from you as far as records and tooth preparation go. The conversation will flow. When you’re doing fixed prosthodontics or making prostheses, you have to realize that you are partnering with someone in the laboratory. That person is your colleague—your partner. Once you know the challenges they face and how those challenges can be addressed clinically, you can be the client they want to do great work for because you don’t send them work with the limitations that other clients do. We have to team up with our dental technician colleagues and work together, and it’s an educational process. The benefits of this kind of partnership will roll over to the patient and improve the quality of care you are able to provide.”

Dr Goodacre and Mr Sakamoto have a distinct camaraderie. When discussing specific cases, each man tries to defer full credit for a successful result to the other. In truth, their work is an equal partnership—one that was built with purpose by two professionals who recognize that a successful result relies on careful collaboration.

The mandibular left first molar was restored using a metal-ceramic crown with a porcelain margin. Both the overall form and appearance are remarkably like a natural tooth but recreated with dental porcelain veneering a metal substructure. Note how Mr Sakamoto has harmonized the appearance with the adjacent natural tooth (mandibular left second premolar). When viewing the intaglio surface, the form of the porcelain margin is visible. The ceramic margin was positioned well past the mesial proximal contact area to hide the metal substructure from view. (Courtesy of Dr Charles Goodacre and Mr Satoshi Sakamoto.)

“I’ll have Satoshi come up and we’ll look at the patient together,” Dr Goodacre says. “Satoshi will take some pictures and study them to determine, based on his experiences, which material will provide the most esthetic result based on each individual tooth.” Dr Goodacre admits that their geographic proximity facilitates a closer partnership than a traditional situation would. “When he was working at Ultimate Styles in Irvine, California and couldn’t come in personally, we communicated using a lot of photos and written information and that worked well. It’s perfectly appropriate to have a patient go to a dental laboratory for a consultation, but if that’s not available you can work it out through a lot of photos and personal contact, back and forth. The key to having a good relationship between the technician and the clinician is two-way communication. I also always send Satoshi photos of the completed treatment so he can see the results of his work, and that’s something a lot of dentists don’t take the time to do. It’s a team effort, and you need to take the time to show your technician when they’ve done a nice job.”

This positive feedback can be seen as sharing credit where credit is due, but Dr Goodacre also emphasizes how important contact at the end of treatment can be if the result is less than optimal. “If something isn’t quite right and you have to do it again,” he says, “you want documentation that you can evaluate and learn from for the next one. We’ve had a few of those over the years—the first restoration doesn’t work out, so you do another one and get a better result with that one.”

“Actually,” Mr Sakamoto interjects, “I have done many metal-ceramic crowns for Dr Goodacre but hardly any redos, because the records Dr Goodacre sends are correct. If I can start with good information, I can do my best work. That is why we can get such good results in most cases.”

“Colleagues I know,” Dr Naylor adds, “they have a rapport with their lab. Clinicians should pick up the phone and talk to their laboratory technician and collaborate, so the laboratory can feel like they can converse with the clinician without fear of losing the client if they say something critical. You have to be able to accept criticism from anybody, and that person needs to be able to tell you things like, ‘Well, Doc, to be honest the impression wasn’t that great, and we couldn’t read the margins,’ or ‘We tried our best, but you didn’t have enough occlusal reduction, so that’s the best we could do for the occlusal anatomy.’ And the dentist should say, ‘Well gosh, next time call me if you see a problem, and then I’ll decide based on the patient whether I can re-prepare the tooth or if we need to change the design of the restoration.’ We have to rely on our colleagues in the field of dental technology because this is their area of expertise, so let’s facilitate that kind of dialogue. This communication is especially important in metal-ceramic cases because so many clinicians just don’t have that technical experience anymore.”

Examples of Success

One of the most complicated yet esthetically rewarding types of metal-ceramic restorations is the porcelain-margin restoration, which can satisfy the esthetic requirements needed to restore teeth in the anterior region. Mr Sakamoto describes the technical considerations involved in making these highly esthetic restorations.

Direct and mirrored views of the intaglio and occlusal surfaces of a metal-ceramic restoration with a 360-degree porcelain margin created for a maxillary right first premolar. The restoration presents with lifelike dental morphology and no externally visible metal. (Courtesy of Dr Charles J. Goodacre and Mr Satoshi Sakamoto.)

“These restorations have a 360-degree porcelain margin,” he explains, “and the porcelain margin needs to be perfect. I bake the porcelain margin four or five times to eliminate all shrinkage. Timewise, I can spend up to 2 hours just baking the porcelain margin. Then I can start on the opacious body, the regular body, and the incisal body. The weak point for metal-ceramic restorations is the opaqueness, so the most important part of making these restorations esthetic is the gradation from that opaque layer using opaque modifier. It’s kind of like how you see a drawing or picture that looks like it’s three-dimensional, when in reality it is a two-dimensional image—that’s the same thing as what I do with the opaque layer. The body of the tooth should be warmer, while the incisal layer should be bluish or grayish. Then I create the internal structure and use an internal stain to characterize the tooth. The final porcelain stage is a clear porcelain over the incisal structure to mimic natural tooth enamel. After this bakes and I finish grinding and adjustment, I polish, glaze, and polish again—it is important to polish after the glaze so you can achieve a natural luster that matches with the adjacent teeth, otherwise the result will not be esthetic.”

Here are a few more examples that represent the high level of esthetics that can be achieved using porcelain-margin restorations:

(left) Facial view of a defective metal-ceramic crown on the maxillary right central incisor. Note the high value of the ceramic, absence of surface texture and incisal translucency, facial overlap, gingival recession, and the display of metal at the cervical margin. (right) The defective restoration was replaced with a metal-ceramic porcelain-margin restoration. Note the corrections made to the outline form (no overlap needed), color, surface texture, incisal translucency, and the gingival margin placement. The soft tissue responded positively to the highly glazed porcelain. (Courtesy of Dr Charles J. Goodacre and Mr Satoshi Sakamoto.)

The mandibular right first molar was restored with a metal-ceramic porcelain-margin restoration next to an all-ceramic crown on the second premolar. Note the positive soft tissue response to both restorations and the harmony of the esthetic outcomes. The metal coping was designed to extend the porcelain margin lingual to the proximal contacts for maximum esthetics. Courtesy of Dr Charles J. Goodacre and Mr Satoshi Sakamoto.)

(left) Facial view of a metal-ceramic restoration for a maxillary premolar. (right) Direct and mirror view of the occlusal surface with its excellent characterization and esthetic occlusal morphology. (Courtesy of Dr Charles Goodacre and Mr Satoshi Sakamoto.)

The Future of Metal-Ceramic Technology

So with new all-ceramic systems cropping up every year and education programs that are unlikely to revert back to old ways, what does the future have in store for metal-ceramic technology?

“I don’t have a crystal ball,” Dr Naylor says, “however, I do see that while the trend in some commercial laboratories is an increase in all-ceramic technology and a decrease in metal-ceramic technology, we have to bear in mind that the patient population is ever increasing—even though the percentage and proportion may decrease, if you look at the number of individual patients there is still a huge demand for metal-ceramics. And I think we’ll see continued demand because the parameters of the mouth are not going to change: there will always be short crowns, there will always be bruxers, there will always be patients who may not be the best candidates for all-ceramic systems. We need to have both all-ceramic and metal-ceramic in our armamentarium. A master ceramist like Mr Sakamoto can layer a metal-ceramic restoration internally to develop a very lifelike restoration, whereas with all-ceramic you have a core, you have a veneer, you have to worry about compatibility between the core and the veneer, and then you have to color it externally. Will that be just as attractive and have the longevity of a metal-ceramic restoration? We’ll find out in time. With metal-ceramic technology, we already have a good thing—we just have to maintain it. With all-ceramic systems, we’re learning as we go how to improve them, identifying their weaknesses so we can try to overcome them, and improving their predictability. That’s what we have to look forward to.

“Whatever you’re using, just use it well,” Dr Naylor concludes. “Make sure it’s appropriate for the environment in which it’s being placed. One of the main things we’re hoping to achieve with this edition of the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology is to show people that metal-ceramic technology has an esthetic range that is greater than they realize, but neither metal-ceramics or all-ceramics is absolute or good for every situation. I believe in relying on the good professional judgment of the clinician to identify which material has the greatest likelihood of providing the outcome that the patient is expecting and that the clinician hopes to achieve. You have to judge each clinical case on its merits and limitations, then prescribe the most appropriate treatment. We just want to show that if you plan properly and take these clinical steps, and if your laboratory has a talented ceramist following some very exacting procedures, you can achieve an esthetic outcome with metal-ceramics—probably one that you didn’t think was possible outside of all-ceramic systems. You don’t have to settle for a material that will look good but won’t perform properly, nor do you have to settle for a material that will work well but won’t look good. With the instructions in this book, you can make the material that works look great.”

The Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition, which includes several stunning cases contributed by Dr Goodacre and Mr Sakamoto, puts technical concerns into a clinical perspective and can be used to create valuable common ground between clinicians in the dental practice and technicians in the dental lab. Whether you’re a clinician looking to expand your material options by improving the esthetic quality of your metal-ceramic restorations or a technician hoping to master both the science and art of metal-ceramic technology, Dr Naylor’s book provides the detailed instructions and expert tips necessary to succeed. The rest is up to you.

Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition

Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition

W. Patrick Naylor

For 25 years, the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology has been an essential textbook, and this revised edition underscores its import to the discipline. The author expertly outlines the history and theory behind metal-ceramic restorations and then guides readers through each step of the fabrication process. Although many students do not realize the esthetic possibilities of metal-ceramic technology, this book illustrates how to achieve esthetic results to rival those of all-ceramic materials through treatment planning, clinical procedures, and dental laboratory steps executed at their highest levels. New to this edition are an expanded illustrated glossary, a simplified four-step buttonless technique, fresh analysis of bonding mechanisms, and a full chapter on the esthetic porcelain-margin restoration. Whether you are providing patients with esthetic fixed prosthodontics or are responsible for fabricating lifelike restorations in the dental laboratory, this book can serve as a valuable resource.

Also, for those we who wish to use the buttonless casting technique as described in the textbook, check out the Wax Pattern Alloy Converter App. This easy to use, well-designed app is available through Apple.

240 pp; 617 illus; ©2018; ISBN 978-0-86715-752-9 (B7529); US $98

W. Patrick Naylor, DDS, MPH, MS, is Adjunct Professor of Restorative Dentistry and former Associate Dean for Advanced Dental Education at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in Loma Linda, California. He completed advanced education programs in prosthodontics, dental public health, and dental materials. In 2000, Dr Naylor retired from the United States Air Force, having served as a prosthodontist (1981 to 2000) and linguist (1968 to 1972). Dr Naylor has written several books, book chapters, and scientific articles, including the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology (Quintessence, 2018). He maintains membership in numerous dental organizations and societies and lectures on topics pertaining to prosthodontics, dental technology, and practice management.

W. Patrick Naylor, DDS, MPH, MS, is Adjunct Professor of Restorative Dentistry and former Associate Dean for Advanced Dental Education at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in Loma Linda, California. He completed advanced education programs in prosthodontics, dental public health, and dental materials. In 2000, Dr Naylor retired from the United States Air Force, having served as a prosthodontist (1981 to 2000) and linguist (1968 to 1972). Dr Naylor has written several books, book chapters, and scientific articles, including the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology (Quintessence, 2018). He maintains membership in numerous dental organizations and societies and lectures on topics pertaining to prosthodontics, dental technology, and practice management.

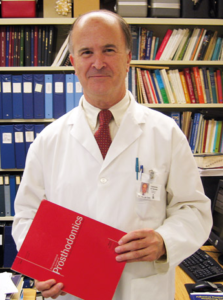

Charles J. Goodacre, DDS, MSD, is Distinguished Professor of Restorative Dentistry at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry. He received his DDS from the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in 1971 and his MSD in prosthodontics and dental materials from Indiana University School of Dentistry in 1974. He served as Chairman of the Department of Prosthodontics at Indiana University, and as Dean of the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry from 1994 to 2013. He has received numerous awards throughout his career, including the Distinguished Service Award from the Academy of Prosthodontics and the Dan Gordon Lifetime Achievement Award from the American College of Prosthodontics in 2014. He has authored over 200 publications, textbooks, and textbook chapters, and contributed numerous cases to the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition (Quintessence, 2018). Dr Goodacre maintains a part-time private practice limited to prosthodontics and has given more than 500 invited presentations.

Charles J. Goodacre, DDS, MSD, is Distinguished Professor of Restorative Dentistry at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry. He received his DDS from the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in 1971 and his MSD in prosthodontics and dental materials from Indiana University School of Dentistry in 1974. He served as Chairman of the Department of Prosthodontics at Indiana University, and as Dean of the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry from 1994 to 2013. He has received numerous awards throughout his career, including the Distinguished Service Award from the Academy of Prosthodontics and the Dan Gordon Lifetime Achievement Award from the American College of Prosthodontics in 2014. He has authored over 200 publications, textbooks, and textbook chapters, and contributed numerous cases to the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition (Quintessence, 2018). Dr Goodacre maintains a part-time private practice limited to prosthodontics and has given more than 500 invited presentations.

Satoshi Sakamoto, MDT, studied dental technology at the Osaka Dental University School of Dental Technology in Japan. He started his career as the technical manager at the Sakamoto Dental Technology Training Center in Japan before moving to the United States in 2002, where he served as the technical manager at Ultimate Styles Dental Laboratory in Irvine, California, from 2002 to 2010. In 2010, he joined the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry as Master Dental Technician. Mr Sakamoto contributed numerous cases to the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition (Quintessence, 2018) and lectures on topics pertaining to dental technology.

Satoshi Sakamoto, MDT, studied dental technology at the Osaka Dental University School of Dental Technology in Japan. He started his career as the technical manager at the Sakamoto Dental Technology Training Center in Japan before moving to the United States in 2002, where he served as the technical manager at Ultimate Styles Dental Laboratory in Irvine, California, from 2002 to 2010. In 2010, he joined the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry as Master Dental Technician. Mr Sakamoto contributed numerous cases to the Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition (Quintessence, 2018) and lectures on topics pertaining to dental technology.

Contemporary Restoration of Endodontically Treated Teeth: Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment Planning

Contemporary Restoration of Endodontically Treated Teeth: Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Treatment Planning Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry: Material Selection and Technique, Third Edition

Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry: Material Selection and Technique, Third Edition Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition

Introduction to Metal-Ceramic Technology, Third Edition Essentials of Maxillary Sinus Augmentation

Essentials of Maxillary Sinus Augmentation RBFDPs: Resin-Bonded Fixed Dental Prostheses

RBFDPs: Resin-Bonded Fixed Dental Prostheses

Brooke Blicher, DMD

Brooke Blicher, DMD Robert E. Marx, DDS

Robert E. Marx, DDS

Douglas A. Terry, DDS

Douglas A. Terry, DDS John A. Khademi, DDS, MS

John A. Khademi, DDS, MS Matthew Mizukawa, DDS

Matthew Mizukawa, DDS Richard Rubinstein, DDS, MS, FACD

Richard Rubinstein, DDS, MS, FACD

W. Patrick Naylor, DDS, MPH, MS, is Adjunct Professor of Restorative Dentistry and former Associate Dean for Advanced Dental Education at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in Loma Linda, California. He completed advanced education programs in prosthodontics, dental public health, and dental materials. In 2000, Dr Naylor retired from the United States Air Force, having served as a prosthodontist (1981 to 2000) and linguist (1968 to 1972). Dr Naylor has written several books, book chapters, and scientific articles, including the

W. Patrick Naylor, DDS, MPH, MS, is Adjunct Professor of Restorative Dentistry and former Associate Dean for Advanced Dental Education at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in Loma Linda, California. He completed advanced education programs in prosthodontics, dental public health, and dental materials. In 2000, Dr Naylor retired from the United States Air Force, having served as a prosthodontist (1981 to 2000) and linguist (1968 to 1972). Dr Naylor has written several books, book chapters, and scientific articles, including the  Charles J. Goodacre, DDS, MSD, is Distinguished Professor of Restorative Dentistry at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry. He received his DDS from the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in 1971 and his MSD in prosthodontics and dental materials from Indiana University School of Dentistry in 1974. He served as Chairman of the Department of Prosthodontics at Indiana University, and as Dean of the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry from 1994 to 2013. He has received numerous awards throughout his career, including the Distinguished Service Award from the Academy of Prosthodontics and the Dan Gordon Lifetime Achievement Award from the American College of Prosthodontics in 2014. He has authored over 200 publications, textbooks, and textbook chapters, and contributed numerous cases to the

Charles J. Goodacre, DDS, MSD, is Distinguished Professor of Restorative Dentistry at the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry. He received his DDS from the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry in 1971 and his MSD in prosthodontics and dental materials from Indiana University School of Dentistry in 1974. He served as Chairman of the Department of Prosthodontics at Indiana University, and as Dean of the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry from 1994 to 2013. He has received numerous awards throughout his career, including the Distinguished Service Award from the Academy of Prosthodontics and the Dan Gordon Lifetime Achievement Award from the American College of Prosthodontics in 2014. He has authored over 200 publications, textbooks, and textbook chapters, and contributed numerous cases to the  Satoshi Sakamoto, MDT, studied dental technology at the Osaka Dental University School of Dental Technology in Japan. He started his career as the technical manager at the Sakamoto Dental Technology Training Center in Japan before moving to the United States in 2002, where he served as the technical manager at Ultimate Styles Dental Laboratory in Irvine, California, from 2002 to 2010. In 2010, he joined the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry as Master Dental Technician. Mr Sakamoto contributed numerous cases to the

Satoshi Sakamoto, MDT, studied dental technology at the Osaka Dental University School of Dental Technology in Japan. He started his career as the technical manager at the Sakamoto Dental Technology Training Center in Japan before moving to the United States in 2002, where he served as the technical manager at Ultimate Styles Dental Laboratory in Irvine, California, from 2002 to 2010. In 2010, he joined the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry as Master Dental Technician. Mr Sakamoto contributed numerous cases to the